The British Library reading room smelled like old pages. I stared at the stack of women’s history books I had ordered—not too many, I reassured myself, not too overwhelming. The one on the bottom was the most unusual: hard-backed and bound in a worn, blue fabric, with yellowing, deckled edges. I opened it first and found virtually two hundred sheets of tiny script—in Yiddish. It was a language I knew but hadn’t used in more than fifteen years. I nearly returned it to the stacks unread. But some urge pushed me to read on, so, I glanced at a few pages. And then a few more. I’d expected to find dull, hagiographic mourning and vague, Talmudic discussions of female strength and valor. But instead—women, sabotage, rifles, disguise, dynamite. I’d discovered a thriller.

Could this be true?

I was stunned.

*

I had been searching for strong Jewish women.

In my twenties, in the early 2000s, I lived in London, working as an art historian by day and a comedian by night. In both spheres, my Jewish identity became an issue. Underhanded, jokey remarks about my semitic appearance and mannerisms were common from academics, gallerists, audiences, fellow performers, and producers alike. Gradually, I began to understand that it was jarring to the Brits that I wore my Jewishness so openly, so casually. I grew up in a tight-knit Jewish community in Canada and then attended college in the northeast United States. In neither place was my background unusual; I didn’t have separate private and public personas. But in England, to be so “out” with my otherness, well, this seemed brash and caused discomfort. Shocked once I figured this out, I felt paralyzed by self-consciousness. I was not sure how to handle it: Ignore? Joke back? Be cautious? Overreact? Underreact? Go undercover and assume a dual identity? Flee?

My genes were stamped—even altered, as neuroscientists now suggest—by trauma. I grew up in an aura of victimization and fear.I turned to art and research to help resolve this question and penned a performance piece about Jewish female identity and the emotional legacy of trauma as it passed over generations. My role model for Jewish female bravado was Hannah Senesh, one of the few female resisters in World War II not lost to history. As a child, I attended a secular Jewish school—its philosophies rooted in Polish Jewish movements—where we studied Hebrew poetry and Yiddish novels. In my fifth-grade Yiddish class, we read about Hannah and how, as a twenty-two-year-old in Palestine, she joined the British paratroopers fighting the Nazis and returned to Europe to help the resistance. She didn’t succeed at her mission but did succeed in inspiring courage. At her execution, she refused a blindfold, insisting on staring at the bullet straight on. Hannah faced the truth, lived and died for her convictions, and took pride in openly being just who she was.

That spring of 2007, I was at London’s British Library, looking for information on Senesh, seeking nuanced discussions about her character. It turned out there weren’t many books about her, so I ordered any that mentioned her name. One of them happened to be in Yiddish. I almost put it back.

Instead, I picked up Freuen in di Ghettos (Women in the Ghettos), published in New York in 1946, and flipped through the pages. In this 185-page anthology, Hannah was mentioned only in the last chapter. Before that, 170 pages were filled with stories of other women—dozens of unknown young Jews who fought in the resistance against the Nazis, mainly from inside the Polish ghettos. These “ghetto girls” paid off Gestapo guards, hid revolvers in loaves of bread, and helped build systems of underground bunkers. They flirted with Nazis, bought them off with wine, whiskey, and pastry, and, with stealth, shot and killed them. They carried out espionage missions for Moscow, distributed fake IDs and underground flyers, and were bearers of the truth about what was happening to the Jews. They helped the sick and taught the children; they bombed German train lines and blew up Vilna’s electric supply. They dressed up as non-Jews, worked as maids on the Aryan side of town, and helped Jews escape the ghettos through canals and chimneys, by digging holes in walls and crawling across rooftops. They bribed executioners, wrote underground radio bulletins, upheld group morale, negotiated with Polish landowners, tricked the Gestapo into carrying their luggage filled with weapons, initiated a group of anti-Nazi Nazis, and, of course, took care of most of the underground’s admin.

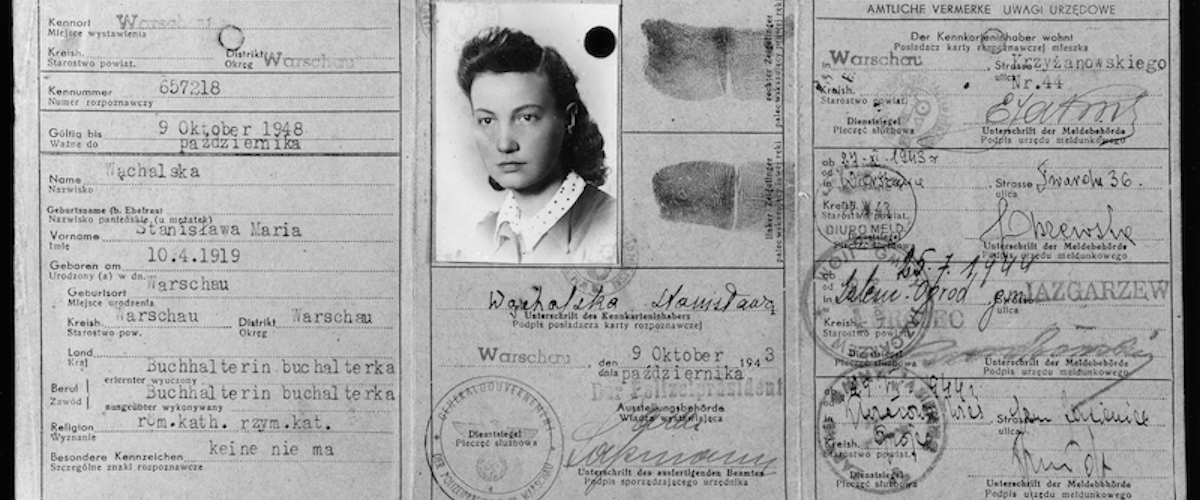

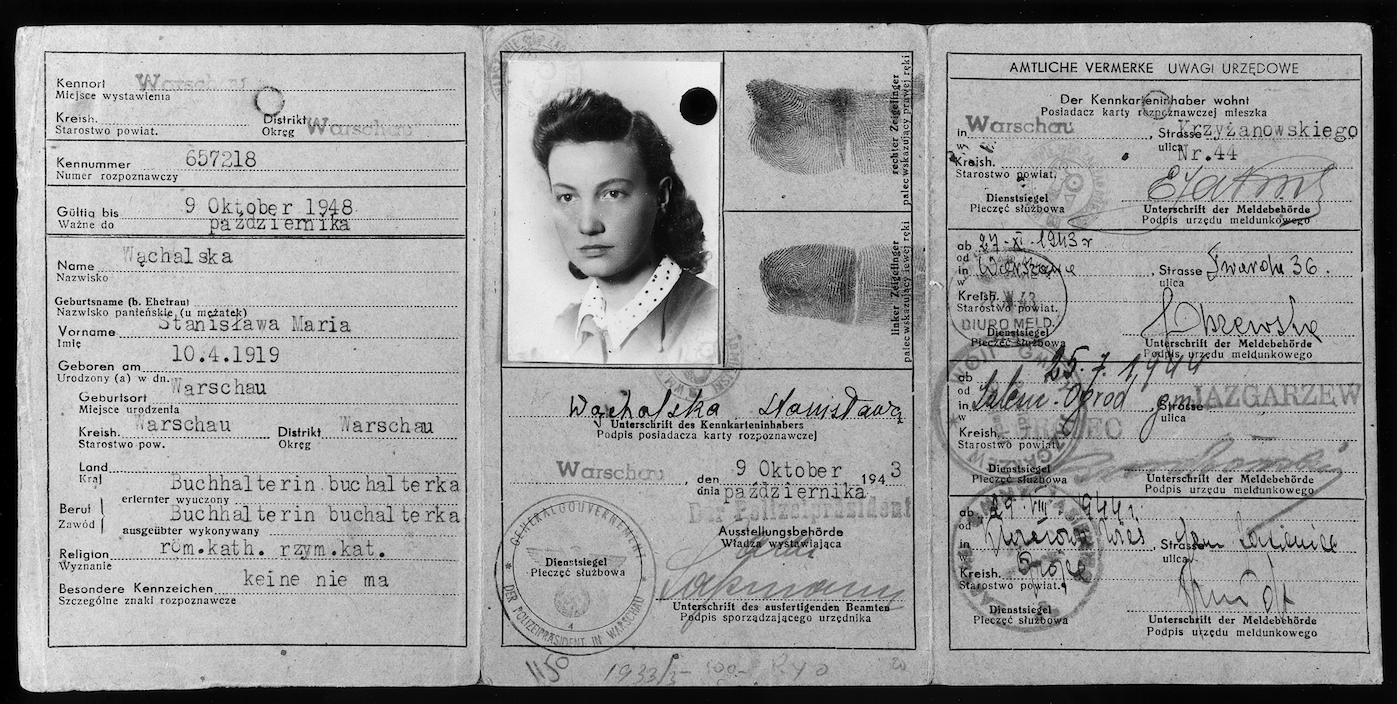

Vladka Meed’s false identification card, issued in the name of Stanisława Wąchalska, 1943. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Benjamin [Miedzyrzecki] Meed)Despite years of Jewish education, I’d never read accounts like these, astonishing in their details of the quotidian and extraordinary work of woman’s combat. I had no idea how many Jewish women were involved in the resistance effort, nor to what degree.

Vladka Meed’s false identification card, issued in the name of Stanisława Wąchalska, 1943. (United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, courtesy of Benjamin [Miedzyrzecki] Meed)Despite years of Jewish education, I’d never read accounts like these, astonishing in their details of the quotidian and extraordinary work of woman’s combat. I had no idea how many Jewish women were involved in the resistance effort, nor to what degree.

These writings didn’t just amaze me, they touched me personally, upending my understanding of my own history. I come from a family of Polish Jewish Holocaust survivors. My bubbe Zelda (namesake to my eldest daughter) did not fight in the resistance; her successful but tragic escape story shaped my understanding of survival. She—who did not look Jewish, with her high cheekbones and pinched nose—fled occupied Warsaw, swam across rivers, hid in a convent, flirted with a Nazi who turned a blind eye, and was transported in a truck carrying oranges eastward, finally stealing across the Russian border, where her life was saved, ironically, by being forced into Siberian work camps. My bubbe was strong as an ox, but she’d lost her parents and three of her four sisters, all of whom had remained in Warsaw. She’d relay this dreadful story to me every single afternoon as she babysat me after school, tears and fury in her eyes. My Montreal Jewish community was composed largely of Holocaust survivor families; both my family and neighbors’ families were full of similar stories of pain and suffering. My genes were stamped—even altered, as neuroscientists now suggest—by trauma. I grew up in an aura of victimization and fear.

170 pages were filled with stories of other women—dozens of unknown young Jews who fought in the resistance against the Nazis, mainly from inside the Polish ghettos.But here, in Freuen in di Ghettos, was a different version of the women-in-war story. I was jolted by these tales of agency. These were women who acted with ferocity and fortitude—even violently—smuggling, gathering intelligence, committing sabotage, and engaging in combat; they were proud of their fire. The writers were not asking for pity but were celebrating active valor and intrepidness. Women, often starving and tortured, were brave and brazen. Several of them had the chance to escape yet did not; some even chose to return and battle. My bubbe was my hero, but what if she’d decided to risk her life by staying and fighting? I was haunted by the question: What would I do in a similar situation? Fight or flight?

*

At first, I imagined that the several dozen resistance operatives mentioned in Freuen comprised the total amount. But as soon as I touched on the topic, extraordinary tales of female fighters crawled out from every corner: archives, catalogues, strangers who emailed me their family stories. I found dozens of women’s memoirs published by small presses, and hundreds of testimonies in Polish, Russian, Hebrew, Yiddish, German, French, Dutch, Danish, Greek, Italian, and English, from the 1940s to today.

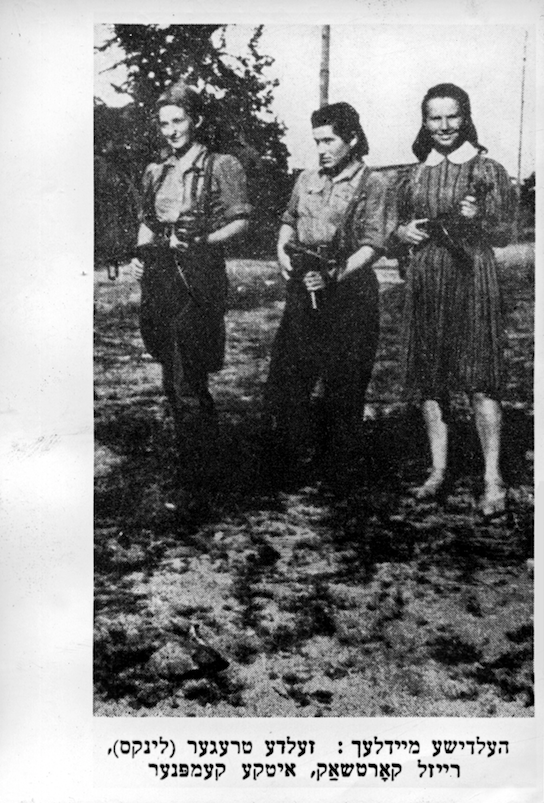

Left to right: Vitka Kempner, Ruzka Korczak, and Zelda Treger. (Courtesy of Yad Vashem Photo Archive, Jerusalem. 2921/209)

Left to right: Vitka Kempner, Ruzka Korczak, and Zelda Treger. (Courtesy of Yad Vashem Photo Archive, Jerusalem. 2921/209)

Holocaust scholars have debated what “counts” as an act of Jewish resistance. Many take it at its most broad definition: any action that affirmed the humanity of a Jew; any solitary or collaborative deed that even unintentionally defied Nazi policy or ideology, including simply staying alive. Others feel that too general a definition diminishes those who risked their lives to actively defy a regime, and that there is a distinction between resistance and resilience.

The rebellious acts that I discovered among Jewish women in Poland, my country of focus, spanned the gamut, from those involving complex planning and elaborate forethought, like setting off large quantities of TNT, to those that were spontaneous and simple, even slapstick-like, involving costumes, dress-up, biting and scratching, wiggling out of Nazis’ arms. For many, the goal was to rescue Jews; for others, to die with and leave a legacy of dignity. Freuen highlights the activity of female “ghetto fighters”: underground operatives who emerged from the Jewish youth group movements and worked in the ghettos. These young women were combatants, editors of underground bulletins, and social activists. In particular, women made up the vast majority of “couriers,” a specific role at the heart of operations. They disguised themselves as non-Jews and traveled between locked ghettos and towns, smuggling people, cash, documents, information, and weapons, many of which they had obtained themselves.

As soon as I touched on the topic, extraordinary tales of female fighters crawled out from every corner.In addition to ghetto fighters, Jewish women fled to the forests and enlisted in partisan units, carrying out sabotage and intelligence missions. Some acts of resistance occurred as “unorganized” one-offs. Several Polish Jewish women joined foreign resistance units, while others worked with the Polish underground. Women established rescue networks to help fellow Jews hide or escape. Finally, they resisted morally, spiritually, and culturally by concealing their identities, distributing Jewish books, telling jokes during transports to relieve fear, hugging barrack-mates to keep them warm, and setting up soup kitchens for orphans. At times this last activity was organized, public, and illegal; at others, it was personal and intimate.

Courier Hela Schüpper (left) and Akiva leader Shoshana Langer disguised as Christians on the Aryan side of Warsaw, June 26, 1943. (Courtesy of Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum, Photo Archive)

Courier Hela Schüpper (left) and Akiva leader Shoshana Langer disguised as Christians on the Aryan side of Warsaw, June 26, 1943. (Courtesy of Ghetto Fighters’ House Museum, Photo Archive)

Months into my research, I was faced with a writer’s treasure and challenge: I had collected more incredible resistance stories than I ever could have imagined. How would I possibly narrow it down and select my main characters?

Ultimately, I decided to follow my inspiration, Freuen, with its focus on female ghetto fighters from the youth movements Freedom (Dror) and The Young Guard (Hashomer Hatzair). Freuen’s centerpiece and longest contribution was written by a female courier who signed her name “Renia K.” I was intimately drawn to Renia—not for being the most well-known, militant, or charismatic leader, but for the opposite reason. Renia was neither an idealist nor a revolutionary but a savvy, middle-class girl who happened to find herself in a sudden and unrelenting nightmare. She rose to the occasion, fueled by an inner sense of justice and by anger. I was enthralled by her formidable tales of stealing across borders and smuggling grenades, and by the detailed descriptions of her undercover missions. At age twenty, Renia recorded her experience of the preceding five years with even-keeled and reflective prose, vivid with quick characterizations, frank impressions, and even wit.

Later, I found out that Renia’s writings in Freuen were excerpted from a long memoir that had been penned in Polish and published in Hebrew in Palestine in 1945. Her book was one of the first (some say the first) full-length personal accounts of the Holocaust. In 1947 a Jewish press in downtown New York released its English version with an introduction by an eminent translator. But soon after, the book and its world fell into obscurity. I have come across Renia only in passing mentions or scholarly annotations. Here I lift her story from the footnotes to the text, unveiling this anonymous Jewish woman who displayed acts of astonishing bravery. I have interwoven into Renia’s story tales of Polish Jewish resisters from different underground movements and with diverse missions, all to show the breadth and scope of female courage.

_______________________________________

From the book THE LIGHT OF DAYS: The Untold Story of Women Resistance Fighters in Hitler’s Ghettos by Judy Batalion. Copyright © 2021 by Judy Batalion. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, An Imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.